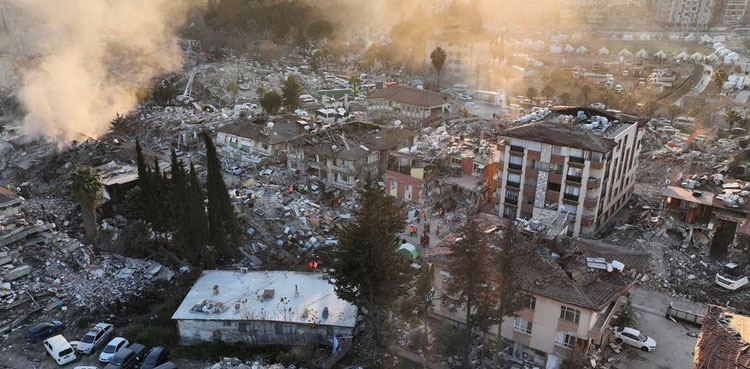

The recent devastating earthquake in Turkiye has once again underlined the frequency of natural disasters that have ravaged many parts of the globe. The most important factor that comes out of such disasters is strengthening the rehabilitation practices all over the world as this is the only way forward. Climate change falls in the same category and requires extra efforts to ensure that the outcome of disasters associated with it is mitigated.

The disaster issue is serious and need tremendous resources to handle it adequately and the main consideration is finance. Finance is therefore rightly the core issue and the recent developments in this regard have compelled the US and other rich countries to undertake parleys about it.

The need is to focus on the three big problems with how climate finance is administered today are the pandemic recession sapped enthusiasm and budgets for climate finance from rich countries.

The issue that many now focus on is not the climate change that is now a given but the effort taken to mitigate its effects. It is very obvious that along with many forms of efforts needed for tackling the subject, the most potent is the availability of financial resources to enable institutions that are mandated to fight it.

The way-out adopted in this respect is full of compromises and that is the only apparently functional method for handling the matter amicably.

It was in this context that the 2015 Paris climate agreement is built on a central trade-off as all countries will follow up plans to cut their carbon footprint but only if rich countries, which bear the most responsibility for causing the crisis, cough up cash for their poorer neighbours, the ones that bear the brunt. But as the volume of climate finance lags behind, rich countries are failing to grasp their own economic interests in protecting poor ones.

The target usually cited for climate finance transfers is $100 billion per year which rich countries committed in 2009 to raise by 2020. A new analysis attempts to capture the full amount of public and private spending on climate adaptation and mitigation measures globally.

It found that tracked climate finance—including what poor countries pay out of their own pockets, what rich countries spend within their own borders, and what corporations spend for their own benefit went up and though this sum may seem impressive but compared to the $100 billion target, what actually needed is a total of at least $4.13 trillion by 2030 for the world to be on track for the Paris Agreement goal to limit warming to 1.5 C. It is therefore demanded that rich countries must contribute far more.

The cardinal reason for the rich countries not doing more is that they still view and process climate finance as a form of charity or aid. This is obviously a myopic view and reflects badly on the perceptions of the ruling groups there. What is actually needed is that to view climate finance as a strategic investment in protecting the roots of global supply chains. For food, natural resources, textiles, consumer electronics, and other key ingredients of global trade, these roots often originate in climate-vulnerable countries. It is quite obvious that when the roots suffer—when a hurricane destroys a factory, or a drought destroys a harvest—rich countries pay more for everything from restaurant bills to semiconductor chips.

The main reason is that while mitigation investments—a solar farm, for example—tend to present a clear business case, adaptation is unlikely to generate direct profit for investors. Climate finance comes with too many strings attached. 60% of climate finance comes in the form of a loan as opposed to grants or equity. While loans from development banks are typically offered at below-market interest rates, they still create a new debt burden for countries that were already struggling before the pandemic. Moreover, loans should not be counted as climate assistance finance at all since they eventually get repaid to lenders. Ultimately, the solution to all three problems is the same: It’s up to the public sector to pick up the slack—which, again, can ultimately benefit consumers in rich countries by mitigating supply chain price shocks.

Although the vast majority of international public climate finance by dollar volume goes toward mitigation projects, agriculture and other sectors that feed into global supply chains are also common.

These efforts feature support for renewable energy which could represent a market opportunity for clean-tech manufacturers in rich countries. In addition, there are a few projects with a more tenuous link to fighting climate change, including funding for counter-narcotics operations and teacher training.

Individual loans or grants often cover multiple development objectives and may not go entirely to climate-related activity and individual projects may also include a mix of public and private funding. The upshot is that if the volume of climate finance for adaptation is increased, it is already poised to flow into projects with benefits that reach beyond the borders of the recipient country.

from Science and Technology News - Latest science and technology news https://ift.tt/nyLsOW4

via IFTTT